JOHN KOCH: THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

Provincetown Arts Magazine Volume 38, 2023-2024 - By E.J. Kahn III

The Truro studio stands at the top of the driveway, 50 feet or so from a sharp bend in South Pamet Road where the street meets Collins, then veers east towards Ballston Beach. A 13-year-old addition to the garage, the modest concrete-floored space was built on the cheap by local carpenter Malcolm Meldahl — his mother Eleanor was one of the co-founders of the town’s Castle Hill Center for the Arts, just a couple of miles away as the gull flies — using salvaged wood and glass, plenty of glass. The screen door, John Koch remarks as he steps into the room, was once Paul Resika’s.

Behind the studio and the gray-shingled Cape a few yards away — the deep blue of its trim and door hints that there’s someone who cares about color in residence — rises a hillside dominated by pine trees and a carpet of their needles. Thirty-eight years ago, when the then-journalist first moved with his wife and son to the Outer Cape as summer people, the pines might have been described as “scrub”. Not so much these days.

They and the hill have been part of the Cape Cod National Seashore since 1960, and the 63 years of protection from encroachment has nurtured their development. Unlike the houses of the Pamet Valley, frozen in time by same legislation, the pine forest just beyond the Pamet Roads has grown thicker and wilder, gifted by climate change.

Each day, Koch sees this as soon as he enters, framed by a south wall of window and sliding door. An easel is set up between the view and the Resika door, the canvas mounted on it facing inward. On this morning, It’s a work very early in its progress, an outline of what seems to be a posed standing figure. When the artist stops work on any canvas propped here, one imagines his eyes must immediately focus on the outdoors. Knowing too, that he has painted versions of this view more than 100 times in his now 18-year second act as a full-time painter, the imagination is making a pretty good bet.

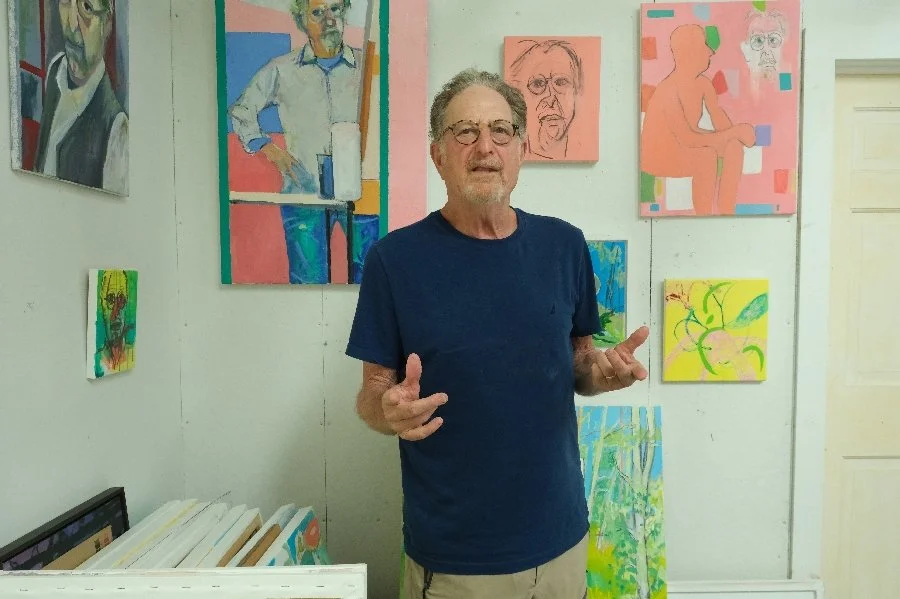

We’re in the studio because, to date, we’ve only talked online for this piece. And although we’ve been neighbors for decades, and been in each others’ homes dozens of times, I have never, in my recollection, visited his workplace. His astonishment has now faded to a shrug. I probably, he has figured, never asked (this is likely, given that I’m shy about entering others’ workspaces). I ask him to pose for me outside, centered in the scene; I will stand next to his easel. He gets it, another shrug, and shuffles outside. The photo is a modest success.

“I was never a photo-realist,” he reflects over coffee, “but in the beginning I painted more of what I saw. As the years passed, I’ve moved to greater abstraction. It’s more exciting, and highly subjective. It reflects what Robert Henry told me and others who’ve taken his workshops, ‘You don’t want the subject matter to take over.’ When you start, you look too much. The subject gets in your way.”

That’s the tension in the making of art, John continues, citing Cezanne as an example and how he would rearrange the landscape he was capturing, moving trees and stones to enhance the image. For Koch, his hill-and-pines works are now “wrestling matches”, and they’re finding an audience. Early this summer, in June, he will have a one-man show — his second — in Truro, and now, in mid-April, on one wall of the studio are several of the paintings that will be hung. Abstract, with patterns suggesting shadows and branches, the largest centered by a tree-like structure more evocative of a medieval eastern European amulet than a backyard conifer, they command one’s attention with both color and texture. “The show will be about my relationship to the natural world,” John concludes. “Everything to do with the natural world. I’m thinking of titling it, ‘Naturish’. But that’s off the record.”

Before becoming a full-time painter, John Koch was one of New England’s most influential journalists covering the arts and culture. For a decade, from 1980 to 1990, he was the editor of the Boston Globe’s Arts section. John knows the rules; you begin with off the record. In this case, too late. No harm done though. Like most of what John has to say, it’s witty and smart.

***

In his studio, when he’s not looking out, Koch is often looking in a mirror. His self-portraits are striking and stylized, with no attempt to be flattering or pretty. Egon Schiele, the Austrian Expressionist who himself was mentored by Gustav Klimt and who died at 28 at the close of World War I, is an inspiration, John tells me. Schiele, critics note, painted himself with “figurative distortions”, and eventually his full-body nudes created — again, not my words — a sexual uproar. Koch has done (and is doing, based on the work in progress I observed) full body nudes too, though never of himself he points out. When I suggested there might be an inquiry into sexuality embodied in this direction, he dismissed the thought. He did note, however, there will be no nudes in the Truro show. I, for one, wish there were.

“I do love the Expressionists. Let’s call it that, rather than abstraction,” John says, correcting my mis-characterization. “There were the American abstract expressionists in the Thirties, Forties and Fifties. And before that, the great German expressionists. Scheile’s painting is just overwhelmingly beautiful, moving, provocative work. Who else? Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Max Beckmann. They have liberated me to do my self-portraits, and experiment with crazy colors. It's a commitment to what might be seen as informality, but is more a freedom. I don't know why people do hyper-realistic work. I admire the skill of the super hyper-realist. But you can use a cell phone with a wonderful camera on it to get the same effects.”

John ticks off more influences and teachers: Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, Maude Morgan, Anne Flash, Amy Wynne, William Papaleo, Laura Shabott, and other artists who have taught at Castle Hill, where virtually every summer since his retirement from the Globe he has taken at least one workshop. Flash, he recalled, used a class to describe how an artist might “mix it up…using different materials and tools.Maybe you've got a few very fine pebbles from the driveway, and you mix them in some kind of archival glue. You're playing with these materials. You're seeing what they can do. You're not thinking how they're gonna inform a painting.” Bob Henry, he reflected “will tell you he hardly ever uses a brush any more for his paintings. He uses a palate knife, a hunting knife, a stick or something he finds in the studio. I found a doormat that was coming apart, took a little piece of it, and discovered it was good for imprinting funny marks on a canvas.”

Amy Wynne gave John a way to turn the isolation of Covid into opportunity. The Rhode Island based artist and teacher directed an online course in the Spring of 2020, and Koch signed up. The pandemic had confined him to an apartment in

Cambridge; his son’s family had moved into the Truro house. Wynne’s ask was that every student create a daily image. “I was sitting in a little third-floor office space with a wonderful view of roofs with a tree behind them. There was a whole world there. The possibilities were almost infinite.” Alternating with self-portraits, Koch posted them on his Facebook page as he delivered them to his teacher. For his followers, it became a remarkable online one-man show (like many if not most artists and writers, John has his own website too; he does not, however, post an image a day there).

Laura Shabott is his most recent muse. He studied with her this winter, and he describes her as “a devotee of abstraction…with the kind of deep knowledge that makes it possible for her to simplify complex ideas and techniques.” Shabott, seeing the acrylic-on-canvas image on Facebook that came out of that workshop, offered similar kudos. “Thank you,” she posted, “for the powerful work you are making.” Two days later, John put up a second version of the same model — it was now a diptych, he offered — and Shabott was almost at a loss for words. “Stunning,” she wrote.

My mistake in looking at Koch’s work, and describing it as “abstraction” rather than “expressionism” (as John corrected me, although he’d used the term too) underscores my ignorance. Even though art appreciation and making art runs in the family — architect grandfather who painted; aunt who spent her life alternating between ceramics, silkscreens and canvas; brother whose cartoons and illustrations became book jackets for another aunt’s authors’ mysteries — I was never able to engage. So I turn to others for apt descriptions. Fortunately, there are a pair of writers on the Outer Cape who’ve successfully made the effort.

“Koch has mastered the art of self-portrayal with no apologies for the varying inner moods or outward appearances of his oft-used subject,” wrote journalist Deborah Minsky a decade ago in the first published assessment of his art, addressing both his self-portraits and the window views. For the former, she analyzed, “His are not simply pretty images as commissioned portraiture tends to be; instead, he paints what he perceives in the reflected face in the mirror… not so much pictures of Koch at certain stages of his life, but engrossing, stand-alone images of a complex man with a story or experience worth sharing.” But she was singularly impressed by the images inspired by his window view, judging that “his most compelling and eye-catching paintings are his semi-abstractions, where he gives himself license to experiment with tone and texture, to dig into inner symbolism and draw out unexpected images.”

Critic Abraham Storer, in a 2022 piece, gave equally high marks to the paintings that will be represented in Koch’s summer show. “There’s an insatiable curiosity to Koch’s work,” Storer noted. “The gridded structure of intersecting trees and shadows is echoed in other paintings, distilled into an abstract language. He’s fearless with materials, scraping paint across surfaces in some works, using knives, brushes, plastic forks, and discarded doormats to make marks. He might have gotten a late start, but there’s no stopping him now.”

***

In 2005, when John Koch retired from journalism and was, as he states on his website, “reborn” as an artist, the transformation was a bit surprising to even those closest to him. “I’d always known he was frustrated that he couldn’t get to do the art he wanted to,” Sharon Basco told me, “so I knew he would spend time on it. I had no idea it would be this much, but perhaps he didn’t either.”

Like her husband, Sharon arrived in Boston as a journalist — she with the alternative weekly Boston Phoenix, he with the old Boston Herald American. They both specialized in arts coverage. John wrote about film (at one point, his reviews were a component of the national Rotten Tomatoes rating system), Sharon about dance. “Alvin Ailey made me a dance critic,” she has said. “Ailey's big bold movements, appealing patterns, and charismatic dancers…enthralled [me] with the absorbing stories his dances told.” As John became an influential figure in Boston culture, overseeing the powerful Globe’s Arts section with a staff of 15 editors and reporters and another dozen or two freelancers, so — in her own way — did Sharon, taking on the Boston Herald’s dance coverage at the invitation of its iconic theater critic Eliot Norton. “I wouldn’t have called us a power couple,” she corrects me, “but we had tickets to every opening.”

By the Nineties, John had transitioned to feature writing and interviews, and Sharon to broadcasting, where she anchored the weekend edition of Monitor Radio underwritten by the Christian Science church. By the end of the decade, with newspapers beginning to encourage early retirements and the Christian Scientists pulling back from programming investments in both tv and radio, John and Sharon were both considering their next acts. For Sharon, it was first with tompaine.com, creating voting rights advocacy content, and then with Spectrum, a National Public Radio publication that had not yet shifted to online. For John, in 2005, it was a chance to live a dream. “I’d had another, interesting earlier life,” he states in his artist’s statement. “But for years this second career, if that’s the word, stirred my dreams… Most of my adult life I was immersed in the arts – but as commentator, writer, critic and editor, not as a practicing artist… As a young person and throughout my journalism career, I nursed, and suppressed, a sharp nagging urge to make art. Over the years, I doodled, and took two or three elementary drawing courses, scarcely slaking the impulse. When I retired from journalism, I was, as I say, reborn.”

More than a decade after writing these words, they continue to resonate. “I'm just incredibly fortunate that I was able to retire at 60 and begin,” Koch explained this spring. “At first I worked in a shared studio. I took lots of classes, studied with remarkable artists. At the Miller Street space in Somerville, each of us worked alone at different times of the day or night. I was both serious and playful, as I think any genuine artist is. I was doing some work on the floor — not borrowing from Jackson Pollock — but it seemed better to have the canvas off its easel. I was doing things that were in my head, that pre-figured my Truro landscapes. There was this feeling of liberation, a summons, a mission, a calling, something bottled in my DNA. I had no ambition to sell a painting or show in an exhibition. It was the work, the process, the alignment with my deepest self.”

The construction of the South Pamet studio followed, as did his first solo show in the gallery of Truro’s Council on Aging in 2012. Eight years later, with the arrival of the pandemic, there was another seismic shift. Sharon Basco recalls a visiting colleague, thinking there might be a local angle to the Covid story, went to Provincetown to do man-on-the-street interviews. Returning to the house, she told Sharon the consensus was there would be a couple of weeks of inconvenience. Bad guess. “We had to adjust,” she remembers, “the Spectrum staff started using iPhones for interviews and file-sharing. Broadcast studios were shutting down and we worked remotely.” Their son Alex, daughter-in-law Claire, and grandson moved into the summer house. Sharon and John holed up in the Cambridge apartment. Months passed, with John painting and drawing what he saw out the window.

“Possibilities presented themselves in a way that they wouldn't under most circumstances,” he explained. “You were anxious about going out to a studio. People weren't going to restaurants and movies. There were limitations by the city or state. But it was freeing and liberating artistically, a series of moments of discovery over a period of time.” That eventually ended with the realization that they could have joined their son’s family without risk. They gave up the apartment, and permanently relocated to the Outer Cape.

***

A year later, there’s a returned sense of normalcy, despite some change. Alex and Claire — he an in-demand theatrical video and lighting designer, she a celebrated manager/creator of immersive theater — have moved back to their own domicile. Sharon, freelance producing since Spectrum went digital, is delving into research around her year — 1967 to 1968 — as an exchange student in Denmark, planning an essay that could morph into a book project. And John is in his studio daily, unless pickleball, appointments or the opportunity to travel (Portugal being the most recent destination) intervene.

Right now, he and I are studying “The Pink Room” which, in fact, is a self-portrait of the artist standing by his easel. He has apparently been working on it for nearly his entire life as a painter. “I began it at the Somerville studio, and it had less color. It was kind of inert. A year or so ago, my neighbor David Perry saw it and said, ‘I think you should go back and work on that.’ I respect and value David’s perspective, so I returned to it with the notion I would play with ‘flash’ colors.”

The result, we can both see, is to have large formal blocs of pink, blue, red and yellow forming the backdrop framing the artist. The colors succeed in bring an energy to the canvas, and they play off against the small dabs of brown, green and more blue that give texture to both the painter’s face and clothing. Koch doubts he would have tried the approach 18 years ago. “You just handle materials a little bit better,” he assesses, “you know a little bit more about color, you draw a little bit better. All of which, in my case, is limited to begin with because, yes, I'm an old man. But a relatively young artist.”

“I really need to learn still more about color,” John continues, and tells a story about Maude Morgan, the esteemed Cambridge-based abstract expressionist who died in 1999 at age 96. Morgan’s circle of friends included some of the premier artists and writers of her era — James Joyce, Frank Stella, Carl Andre, Ernest Hemingway — and John, is his capacity as an interviewer for the Globe Magazine, was able to sit with her and talk.

“I loved her work, and had studied major pieces she’d done that were hung in the Museum of Fine Arts and other galleries,” Koch explains. “Late in life, she was doing simple, powerful, subtle collages. I don’t remember if I was responding to them, or to something she had said, but I asked her — and it’s seems so simple-minded — ‘Do you have a favorite color?’

“‘I do,’ she answered. ‘It’s yellow.’”

John asked why.

“It’s the color of life,” Maude Morgan stated.

Koch pauses, looking around his studio, at the expressionist landscapes and the self-portraits and posed nudes. He has already told me this is more than a workplace, it’s a sanctuary.

“I love the answer,” he concludes, ready to get back to the easel. “There was no more to be said.”

Just more to learn.

An excerpt from…

Art Briefs: An Artistic Dialogue at Seashore Point Gallery

Provincetown Independent – July 2, 2025

By Abraham Storer

Anne Flash and John Koch met in a class at Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill around 10 years ago. The class, taught by Flash, was about “opening up people and resupplying their toolboxes,” says Koch. Flash brought a variety of materials for participants to reconfigure and playfully create with. Since then, they have kept in touch. “I was a big supporter of him during that week,” says Flash, “and he became a big supporter of mine.”

Flash and Koch will present their work in a joint exhibition, “Facing Each Other,” through the end of July at Seashore Point Gallery (100 Alden St., Provincetown). There will be an opening reception on Saturday, July 5 at 5 p.m.

On the work of John Koch:

Koch’s portraits teem with a similar dynamism. His work is united by a porous relationship between drawing and painting and a use of high-key color — but aside from that, just about anything goes. Some paintings depict the artist as a flattened silhouette in a field of geometric shapes. Other images are conversations with other artists, like Lester Johnson and Paul Cezanne. Some are exercises in realism; others are abstract.

It makes sense that both artists rely heavily on drawing, a medium associated with exploration. Koch’s Ou Est La Vie? combines charcoal and paint in a closely cropped self-portrait. His honest, self-searching gaze encapsulates much of what his paintings are about: an artist trying to find his way. It reminds me of something Flash said in her studio when describing how she creates her work: “The images are flowing through me.” She thought the sentiment sounded like a cliché, but I think it’s a perfect concept to keep in mind when looking at this show.

Read the full article here.

An excerpt from…

Celebrating Five Decades of Castle Hill

Provincetown Independent – October 27, 2022

By Abraham Storer

This fall, the 50th anniversary of the Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill has been marked by several group shows celebrating the vast network of artists associated with the center. The current show at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum is the most comprehensive, featuring more than 100 artists.

Presented in salon style, the exhibition includes artworks created in each decade of Castle Hill’s existence. There is no stylistic consistency in the show; the diversity and heterogeneity of the artwork reflects the free-wheeling spirit of the center. Several works in the exhibition were created this year, which speaks to the continued influence of Castle Hill on the creative community of the Outer Cape.

Five artists who made pieces in 2022 reflect on their work and their connection to Castle Hill…

John Koch, Backyard Party.

JOHN KOCH

On his work:

“I owe a huge debt to the view outside my studio. The strata of marks in this painting tells me something about the hillside, and the dynamic of things growing out there. A lot of it is also intuitive. I like the colors; they please me. I play with them. I use combs and toothbrushes and serrated scrapers to make marks. I’m in a place of pleasure and invention, and stuff just happens.”

On Castle Hill:

“Castle Hill in a way is my art school. It has this unpretentious atmosphere where people who are beginners or serious all work together very comfortably and bring very different experiences to their work. This very supportive and fairly loose atmosphere has been a gift to someone like me who started with some enthusiasm but no particular ambitions.”

John Koch Mixes it Up

Provincetown Independent – July 14, 2022

By Abraham Storer

John Koch, Interstices, a 36-by-36-inch acrylic on canvas.

After years as a journalist and arts editor at the Boston Globe, John Koch dove headfirst into the pursuit of painting. The itch had long been there. As a child, he found himself inspired by his grandfather, an artist.

“I loved being in his studio,” Koch recalls. Despite devoting his career to journalism, Koch says, “I knew I would do it when I retired. Art chose me.”

He has made up for lost time and has now been painting for well over a decade. On a recent visit to his Truro studio, canvases ranging from landscapes to collaged abstractions filled the space where he was putting the finishing touches on work for a show opening at the Provincetown Commons on July 12 and continuing through July 24 with a reception on Friday, July 15 from 5 to 7 p.m.

There’s an insatiable curiosity to Koch’s work. In one small landscape, he paints the woods outside his studio. The gridded structure of intersecting trees and shadows is echoed in other paintings, distilled into an abstract language.

He’s fearless with materials, scraping paint across surfaces in some works, using knives, brushes, plastic forks, and discarded doormats to make marks. He moves freely between subjects, from oil paintings of nude models to memory-laden mixed-media collages. He might have gotten a late start, but there’s

no stopping him now.

A Palette of Time, Discipline and Passion

Provincetown Banner – August 2, 2012

By Deborah Minsky

John Koch of Truro knows art and knows what he likes. A former Boston Globe arts editor, over his long career in journalism he was immersed in the arts and visited many studios and reviewed countless shows. Now, in what could be called semi-retirement, Koch is rediscovering his artistic self, putting his own canvases up on the easel as he works at becoming the painter he always wanted to be. Although he is relatively new to creating art, he shows a remarkable flair and innate talent.

He works in a range of media, often in unusual combinations of acrylic, oil, charcoal, pastels and oil sticks, all of which can be seen in his show “John Koch: Landscapes & Head-scapes.” An opening reception takes place from 4 to 6 p.m. Sunday, Aug. 5, in the COA Gallery at the Truro Community Center, 7 Standish Way, North Truro. The show runs through August.

In his studio just off South Pamet Road, he enjoys inspirational views from many angles. The summer home he has shared with his wife, Sharon, for the last 25 years rests snugly against Cape Cod National Seashore land where they will never have to worry about the encroachment of developers or the presence of too-close neighbors. That knowledge allows him to enjoy the timelessness of the surrounding wooded landscape without fearing for its impending demise. His paintings of those outdoor scenes reflect great joy in that security.

Koch has mastered the art of self- portrayal with no apologies for the varying inner moods or outward appearances of his oft-used subject. His are not simply pretty images as commissioned portraiture tends to be; instead, he paints what he perceives in the reflected face in the mirror. Through Koch’s artistry these self-images take on a life of their own, with distinctive, intriguing personalities, not so much pictures of Koch at certain stages of his life, but engrossing, stand-alone images of a complex man with a story or experience worth sharing.

“I don’t do them because of any interest in my own funny face,” he says. “I do them when I can’t really think of what else I want to do. I’m not interested in me as such. I do them as an exercise.”

A gifted draftsman, Koch also draws exquisite sun-dappled trees and sketch- es figures in repose with great grace, but his most compelling and eye-catching paintings are his semi-abstractions, where he gives himself license to experiment with tone and texture, to dig into inner symbolism and draw out unexpected images. Koch has learned well the techniques of under-painting and how to draw the most effect from every inter-play of light and tone. He knows his color values. He is also very modest about his obvious ability, almost in awe of the painterly life as it unfolds to him.

Koch acknowledges local artists who helped him get started. At various times and places — including Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill, Provincetown Art Association and Museum and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown — he has studied with Robert Henry, Selena Trieff, Joyce Zavourskas, Eleanor Meldahl and William Papaleo, to name just a few. He credits artist Anne Flash for encouraging him to “mix it up,” and let loose with varying media and techniques, to really explore his painting surfaces to see what they will reveal to him as the process unfolds.

“The COA exhibit is an astonishing opportunity that came to me out of the blue,” he says. “I owe it all to Eleanor and [her son] Malcolm. I just want to say, because it is true, that I feel very privileged to have this show.”